Chapter Six

Will it be an “ASSET” sale or a “STOCK” sale? The first (and most fundamental) question when structuring either an internal or external transition of any business, is whether it will be structured as an “asset” sale or a “stock” sale. Since most companies are either corporations, or LLCs taxed as a corporation, this discussion will refer to corporations. If your business is a sole proprietorship or partnership, your situation will be similar to an “S” corporation.

Most sales are structured as an “asset” sale. In some cases a “stock” sale is more appropriate, although the parties to the sale may not realize this. There are major legal and tax issues involved, and they impact the buyer and the seller differently. The difference can be profound, with major operational, legal and tax ramifications.

This fundamental decision can become a highly contentious difference between what the buyer and the seller want in the sale!

Buyers: Although it will not always be the case, buyers will usually prefer an “asset” sale structure.

An “asset” sale exposes the buyer to less potential carry-over legal liability than a stock sale, so the starting point recommendation from most attorneys representing the buyer will be an asset sale. The tax effects in an “asset” sale also tend to favor the buyer compared to a stock sale, so most CPA’s for the buyer will also favor an asset sale. Accounting rules for publicly traded corporations favor “asset” sales, so big national buyers favor asset sales.

Although the starting point for most attorneys will be to favor an “asset” sale, the legal issues are complex and varied. There is much more involved than just potential carry-over liability, and other issues can sometimes favor a stock sale instead of an asset sale. For instance, favorable contracts of all kinds with third parties are often much easier to preserve in a stock sale. Legal issues are covered in more detail in other chapters.

Sellers: The decision is not as clear-cut on the seller’s side of the table. In some cases, taxes on the seller will be essentially the same regardless of whether a sale is structured as an “asset” sale or a “stock” sale. In these cases, the seller is usually neutral between an “asset” and a “stock” sale.

In some cases, the seller will be taxed much more heavily in an “asset” sale. In these cases sellers will strongly prefer a “stock” sale. The extra tax can be so high that it will actually kill the deal unless either the sale is structured as a “stock” sale, or some other way can be found to reduce the tax.

There are various ways to mitigate the tax damage; all of which add complexity, and none of which completely eliminate the problem. The simplest solution is to mutually agree to a “stock” sale. The disadvantages to the buyer can be offset by a reduced price.

An overview of the tax issues is provided at the end of this chapter. Ways to potentially mitigate the damage are covered in other chapters.

Basic Steps in an Asset Sale:

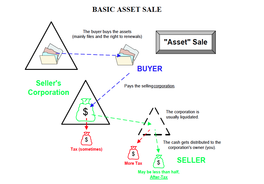

In an “asset” sale, the assets of the corporation are sold directly by the corporation – not by its shareholders personally. Let’s assume for purposes of illustration that the primary asset sold is the company’s customer accounts or book of business (an “intangible” asset) in a heavily intellectual property based business. The stock of the corporation is not sold – that would be a “stock” sale.

The basic steps in a typical “asset” sale by an incorporated business are as follows:

(1) The buyer is often an existing company that is already incorporated. That corporation is the “buyer”; not the shareholder(s) of that corporation. If seller financing is involved, the shareholder(s) of the buying corporation will generally be required to guarantee payment of the purchase.

(1.a.) NOTE: If the buyer is an individual who intends to operate the business as a corporation, that buyer should form the buying corporation PRIOR to the acquisition.

(2) The buying corporation pays the selling corporation for those assets. The money and/or seller-financed promissory Note goes to the corporation, not directly to the selling corporation’s shareholders.

(2.a.) The buying corporation may need to renegotiate various legal agreements, such as leases, contracts with key vendors or customers, etc. These negotiations are often started prior to closing of the sale, particularly if a favorable lease or critical vendor or customer contracts are involved.

(2.b.) The buying corporation becomes the NEW employer of the selling corporation’s employees. New employment contracts should have been presented to the employees prior to closing, with enough time for their attorneys to review the drafts prior to signing. In order to make non-piracy covenants in those new contracts enforceable, the employee should not do any work for their new employer until they have signed their new terms of employment.

(3) Next, the selling corporation pays whatever liabilities it owed at the time of the sale, plus any taxes owed on the sale of its assets. The corporate taxes are owed in the year of sale.

(3.a.) An often overlooked seller obligation is accrued employee vacation, even if the seller keeps its books on a cash basis.

(3.b.) An “S” corporation might not owe much tax; although this is not always the case. Always check with your CPA on this.

(3.c.) If the seller is a “C” corporation, the federal tax at the corporate level is likely to be 34% or more, plus whatever tax your state imposes. Much, but not all, of this draconian extra tax can be mitigated by pre-planning or a more sophisticated structure for the sale.

(4) After taxes and whatever other liabilities the selling corporation may owe are satisfied, that corporation then “liquidates” itself and distributes the remaining after-tax cash and/or promissory Note that it received from the buyer to the selling corporation’s shareholders.

(4.a.) Any remaining assets owned by that corporation that were not included in the sale are also distributed to its shareholders at this time. For instance, the seller’s company car is often in this category.

(5) The shareholders then pay personal capital gains tax on what they received. If significant taxes were owed at the corporate level first (such as with “C” corporations), then this is essentially a second tax on the same sale!

(5.a.) Counting state and federal taxes at both the corporate and personal levels, the combined tax on the seller can easily be over 60% of the total sale price.

Taxes this high can obviously be disastrous to a seller. Worse, the impending tax hit may not be known by the parties until the seller's C.P.A. is brought in just before closing. All parties (particularly the seller) are dismayed by the taxes about to be owed, but it can be difficult to restructure a sale at that late date. But if the tax problem cannot be solved, it can rightfully become a “deal killer”.

Disasters like this can be avoided by advance planning by the seller prior to the sale, and by a more sophisticated sale structure at the time of sale. For instance, if the selling “C” corporation had switched to “S” status 10 years earlier, then most of the problem would have gone away. Likewise, it is often possible to greatly reduce the double tax problem with a more sophisticated sale structure at the time of sale. This is discussed in a later chapter.

When is an Asset Sale “OK” from a Tax Standpoint?

From a tax standpoint, an asset sale is most appropriate when the draconian tax at the corporate level can be avoided. This is most likely when the selling company is either not incorporated at all, or is an “S” corporation that was never a “C” corporation in the first place. In each of these cases, the corporate level income tax on the sale of the book of business can be avoided. There may still be other taxes, but this avoids what is usually the worst tax hit at the

corporate level.

If the selling company is an “S” corporation that used to be a “C” corporation, then the date of the conversion is crucial. A “C” corporation that converts to an “S” corporation must wait 10 years before most of the tax at the corporate level goes away. However, if 10 years have not gone by since the switch, an “S” corporation may have just as big a problem as it would have had if it were still a “C” corporation. For “S” corporations in this situation, the corporate level income tax will be on what the IRS refers to as “built-in gains”.

All shareholders are taxed in an asset sale, even if they are not selling their own shares. Hence, if one shareholder is selling but the business as a whole is not being sold, then an “asset” sale is rarely appropriate. Shareholders not involved in the sale would not appreciate having to pay taxes just because someone else sold. This situation is almost always a “stock” sale of that shareholder’s shares.

Basic Asset Sale Tax Effects on the Buyer

Assume the primary “asset” being sold by a company is its customer accounts. The price paid for this asset will be amortized (i.e., deducted for tax purposes) by the buyer over a 15-year period regardless of the length of time over which payments for it will be made. Obviously, a tax deduction spread out over 15 years is not worth as much as a deduction that the buyer gets to take right away; but it is still worth having.

If the buyer subsequently re-sells that book of business, the amortization that was taken each year will have to be “recaptured”. In most cases, this means the deductions taken each year must be reversed and treated as income in the year of sale. This “phantom income” in the year of the subsequent sale generates tax at the corporate level that must all be paid in the year of that sale! This is a major future tax that the buyer should consider and plan for at the time those customer accounts are originally purchased.

Amortization of intangibles (such as a company’s book of business) is covered by Section 197 of the tax code. In 2005, the rules were changed on how this amortization is “recaptured”. The intent was to collect more money (naturally). Under the new rules, it is very difficult to avoid “recapture” of the entire amount previously amortized when a purchased book of business is resold. Obviously, this has the potential to be a major unexpected tax hit in an

“asset” sale even for an “S” corporation.

There appear to be ways to avoid full amortization recapture. They are more likely to work if they are planned for at the time the accounts are purchased rather than after the fact when they are re-sold. These methods appear to be entirely consistent with tax law, but are a “facts and circumstances” issue that cannot be guaranteed. To your authors’ knowledge, they have not been tested in court.

Basic Asset Sale Tax Effects on the Seller

If the selling corporation is NOT a “C” corporation or an “S” corporation subject to the draconian corporate tax described above, then in most states the corporation itself will not owe income tax on the sale of its assets.

The selling corporation's shareholders will still owe capital gains tax at the personal level. Capital gains tax will be about 20% at the federal level, plus whatever state and local taxes your state imposes. For many sales, an additional Obamacare Net Investment Income Tax of 3.8% will also be included.

If the seller is a "C" corporation, then sellers will be taxed first at the corporate level, and then what’s left will be taxed at the personal level.

The selling corporation will owe corporate income tax on almost the entire amount received. State tax rates vary by state, but the federal tax will be about 34% depending upon the size of the sale. Next, the individual stockholders will then owe capital gains tax on what’s left at the personal level. The state tax will vary, but the federal tax will be about 20% plus a potential Obamacare Net Investment Tax of an additional 3.8%. The combined federal tax will be about 50%. When state and local taxes are added in, the total tax on the seller can easily exceed 60% of the total sale proceeds.

Many sellers would rather not sell at all than pay taxes this high. If the seller has this tax predicament, several basic tools are available to at least partially remedy the situation. They will be explained further in subsequent chapters.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed